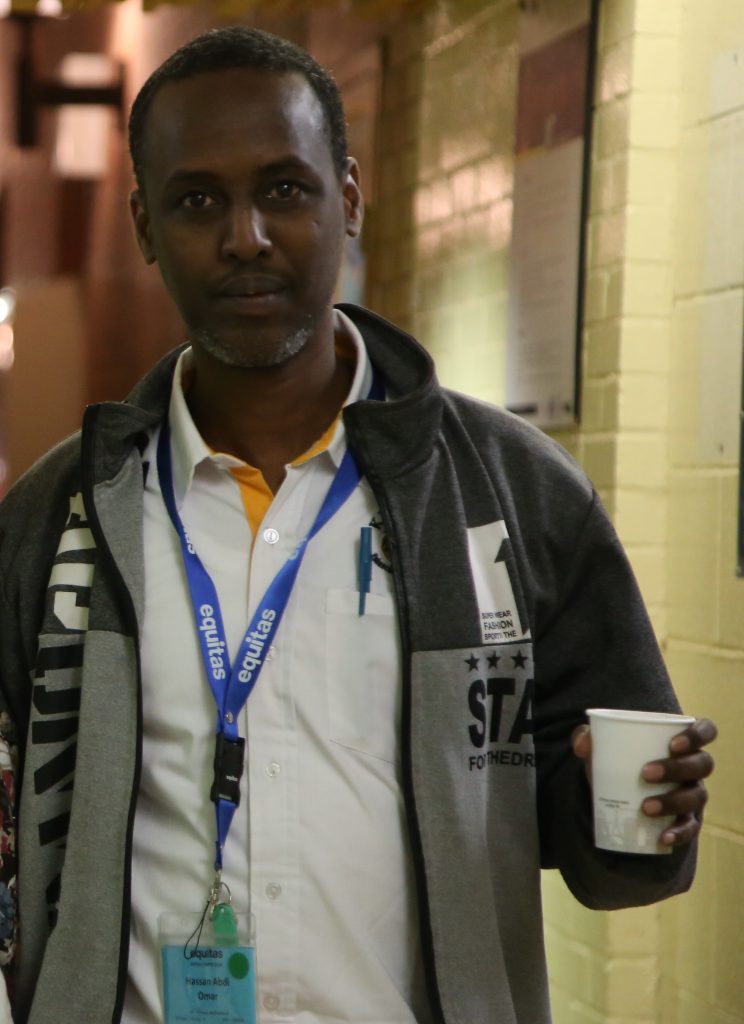

While civil society organizations certainly hold a critical role in the advancement of human rights around the world, it is important also to highlight the work of the national human rights institutions who uphold and defend them. In 2011, the government of Kenya established a watchdog body, called the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), whose primary goals are to monitor institutionalized human rights violations and to promote and protect human rights across the country. Through his work for this commission, Hassan Abdi Omar, a participant at this year’s International Human Rights Training Program (IHRTP), develops human rights curricula and training material to be used throughout the country, contributing to the spread of public education for all.

“In Kenya, a developing country, there are a lot of human rights violations. When people speak up about their rights, for example, use their right to assembly, they are threatened, their lives are threatened. There are parts of Kenya, for example where I come from, where there is no running water, no quality schools. The basic economic and social rights, the right to health, to water, to education, those are the rights we are struggling with. The most basic things that define what is a human being is. When you come from that point, you understand what human rights mean. And as a commission, we are the voices for the voiceless. We are able to tell the government that they are required to provide these things.”

In a country faced with many challenges, the work of the Commission is not easy. As part of their work is based on citizen denunciation of human rights violations, making themselves accessible to all can be difficult. Their work is also heavily jeopardized by the agenda of the Kenyan government itself. Not only are their resources limited, but certain situations cause the government to allow or even perpetrate human rights violations, often in the name of national security. For example, the border dispute with Somalia and the looming presence of terrorist organization Al-Shabaab have caused the Kenyan government to drop its responsibilities relating to human rights recently.

“The government, who is supposed to protect, becomes the principal violator of rights, especially through extrajudicial killings. When people wanted to riot, many died – the police used their bullets. This shows again that they have failed their duty to protect human life when they shoot. These are some of the things that we say are challenges: there is no excuse for a government to abdicate its responsibilities.”

Nonetheless, the achievements of the KNCHR are impressive. As Hassan was preparing to attend this year’s IHRTP, his organization was making recommendations as part of a High Court case regarding abortions in cases of rape, which ruled in favour of the victims in a landmark decision. “We take our protests to the boardrooms,” he says, explaining that they have been working their way closer to the government, decision-making circles and educational institutions of the country, which makes their work more efficient. For instance, the Commission now works with the Kenya School of Government and the Kenya Judicial Training Institute and provides them with basic human rights courses and training material in order to better prepare them for life in the public service and judicial fields. Another initiative they have recently started is the setting up of an SMS and WhatsApp number for the Commission as a way to facilitate communication with citizens living in unreachable regions. From now on, Kenyans who wish to report human rights violations don’t need to physically present their claims to a KNCHR office; they can simply do so on their phones.

Another significant aspect of the Commission’s work is its emphasis on gender equality. Early on in his work in the development of human rights curricula, one of Hassan’s main priorities was the creation of gender-sensitive content.

“We’re sensitive to the material we use for training, we cannot be perceived as if we’re promoting one gender over the other. Also, when we are identifying participants to come to our training, we have to be conscious and make an effort to diversify our participants. At the organization’s level, our chairperson is a woman, two of our commissioners are women – that way, we apply the equal gender rule in our country. At every level, we ensure that there is gender representation because there are issues that are very specific to women – for example, female genital mutilation. When we review policies and laws from the government, and we have to consider whether they are gender-responsive.”

The promotion of gender equality is essential to the fight for human rights in Kenya, which is why Equitas is extending its work to the country. Aiming to support women’s leadership, build the capacity of civil society organizations, and contribute to creating spaces for dialogue with decision-makers, Equitas hopes to empower women and girls and help them foster an environment of equality within their communities.

Supporting human rights education in Kenya is therefore of major importance to the operations of the KNCHR. According to Hassan, building the capacity of his staff and providing them with the right tools to recognize human rights violations and to build defenses against them is the first step to bringing change in his home country, a step which he believes was made possible by attending the IHRTP.

“Charity begins at home, change comes from within. And the IHRTP experience requires a change of mindset – for example, I come from a conservative community. Even as a human rights defender, the LGBTQI community, we don’t talk about it. So it was my first experience interacting with a person who said they are lesbian or gay, to tell me their past and their stories. To me that was an eye-opener, I learned a lot and it has changed my views and perceptions about it. This training was a big opportunity to build the knowledge I need to transfer to the other members of the Commission’s staff. The advantage I have is that some of my colleagues have already done [the Program], so I have two alumni who I can work with. Starting with my department, I have to start having a conversation about what can help and impact in terms of change. Once we are done with that, our content, our training material must be in line with the participatory approach.”

Because of the specific nature of the work achieved by national human rights institutions, their representation and learning experience at the IHRTP is important to the fight for human rights. For this reason, the Max Yalden Foundation, which was set up in honour of the former Chief Commissioner of the Canadian Human Rights Commission and member of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, supports a participant’s attendance to the Program annually. This year, Hassan was awarded this bursary to allow him to continue pursuing human rights education in Kenya.

“It’s been a very good opportunity for me to be here. I built relationships, a network which I will cherish for the rest of my life… I learned a lot in terms of knowledge, skills, experience. Things that I wouldn’t have learned or seen until I came here.”

By Elyette Levy, Communications intern at Equitas