In late 2014, Rosnida Sari, a lecturer at the Ar-Raniry State Islamic University in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, took a group of her students on a voluntary tour of a Protestant church in order to better understand the concept of gender as perceived in the Christian faith and to promote interreligious harmony. After a report about the visit published in an Australian media outlet went viral on social media, Rosnida was accused of trying to convert her students to Christianity. She received hundreds of death threats and was suspended from teaching.

In the Muslim province of Aceh, the only province in Indonesia whose government fully applies Shari’a law, the pushback on Rosnida’s teaching methods was overwhelming. In addition to the conservative reactions of the community members, the authorities accused her of breaking the law and forced her to apologize for her cultural and religious insensitivity.

“My hometown is very strict with the Islamic law. But my students wanted to come to the church, they wanted to learn about gender and how it is taught in the Bible, but people didn’t want to hear it. All they saw were the headlines, and for three years I have not been able to teach because of it. So I had to find my own strategy, my own way to teach about human rights. I don’t teach about gender anymore, my course was given to another person – I can only teach about research and geography.”

Even when she first began teaching, Rosnida’s human rights-related curriculum was limited. With no mention of human rights in courses at all, she has to use terms such as “advocacy” and “equality”. As part of the Department of Community Development, her faculty is the only one in the University to give classes on gender theory.

“The term ‘gender’ is very sensitive. They don’t want to use gender, or even ‘human rights’. Not many people know about human rights because most of them think that it comes from Western society, and that it cannot be adopted to the people [of Indonesia]. We cannot speak actively about human rights, so we have to find our own ways to talk about them.”

Discrimination in Aceh runs deep – not only against non-Muslims, but against people of different ethnicities and sexual orientations as well. For instance, in 2012, Rosnida recalls a government statement to close down churches in her hometown, claiming that the building of churches was illegal. She also explains that, despite the rigorous application of Shari’a law, women of Chinese ethnicity aren’t obligated to wear a hijab based on the assumption that they aren’t of Muslim faith. There have also been institutionalized campaigns against members of the LGBTQI community, specifically trans people, attempting to dissuade citizens from renting out apartments and business spaces to them as a way to drive them out of the province.

Nevertheless, none of this stopped Rosnida from continuing to teach about human rights. By working with organizations outside of her University, she gives lessons and seminars about interfaith issues and women’s movements, often to Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist youth. While she is glad to be given a platform to promote harmony, where she stands with the University still prevents her from co-signing publications, conducting research, and even being part of the Board of organizations she has partnered with for many years.

“I cannot stand up, but what I can do is to transfer my knowledge to the students. My University is very exclusive, only Muslim people can attend, so they don’t know about Christian society, about Buddhism, Hinduism, and they don’t have any other interpretation of the Holy Book. So that’s my duty, to open their minds.”

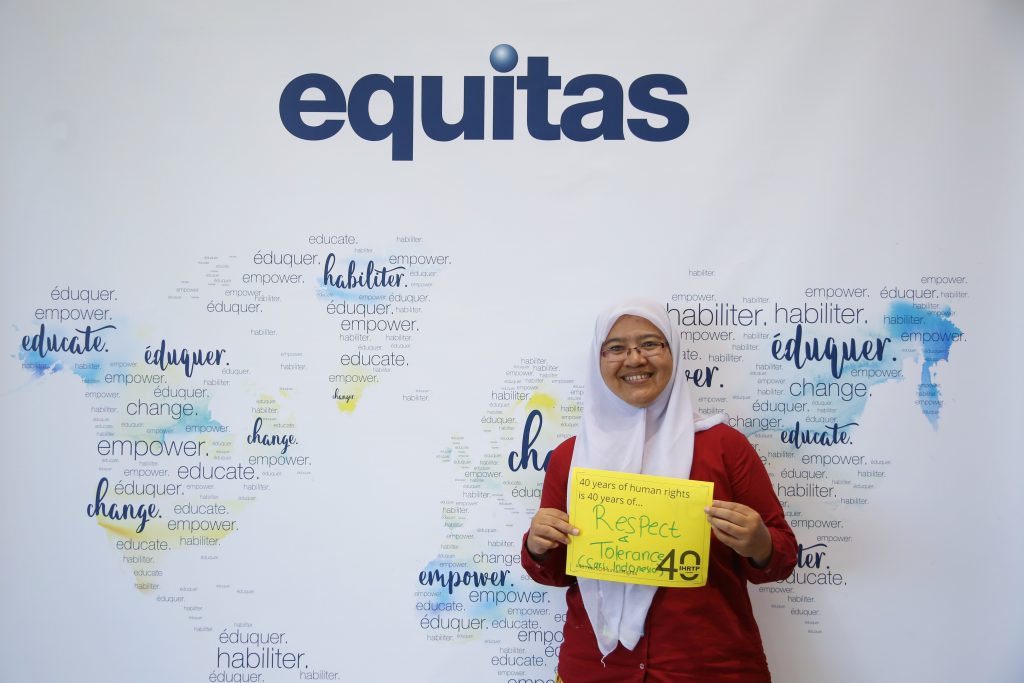

Her passion for what she teaches is also what brought her to the International Human Rights Training Program (IHRTP) this year. Even though she had already contributed to the promotion of peace, women’s empowerment, and interreligious harmony for years, she didn’t fully know what human rights were until she attended the Program.

“I’m so happy to have some material that I can use in my class. I didn’t know about human rights before I did the IHRTP, but I wanted to be involved, I wanted to know more about what they are, what are the UN instruments. In my hometown, because I’m involved in activism, some friends asked me to read their paperwork, write some reports for the [Universal Periodic Review (UPR)]. I didn’t know about the basics to do all that, what the function of it is, so I got to get more insight here.”

Defending human rights is rarely an easy task, and stories like Rosnida’s bitterly serve as a reminder of how dangerous the promotion of peace can be. This is why she was chosen as this year’s recipient of the Brian Bronfman Family Foundation IHRTP bursary, an award created in the name of Brian Bronfman, a man who dedicates his life to promoting peace and mediation, and that was specifically made for participants who advocate for peace through human rights education. In accordance with the Brian Bronfman Family Foundation’s values of intercultural building, conflict resolution, and social harmony, Rosnida’s work stood out for its use of innovative ways to promote peace, non-violence, and diversity, as well as it’s significant impact in her community. Thanks to the support of the Foundation, participants from all around the world continue to have the opportunity to work towards a more peaceful future through human rights education.

By Elyette Levy, Communications intern at Equitas