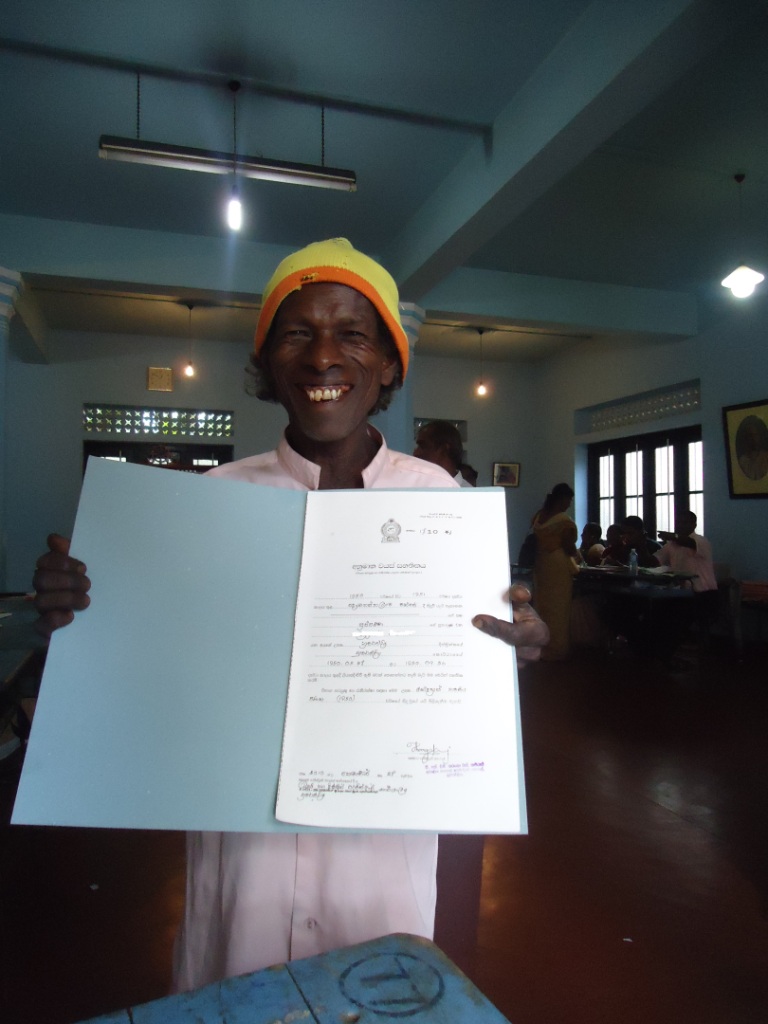

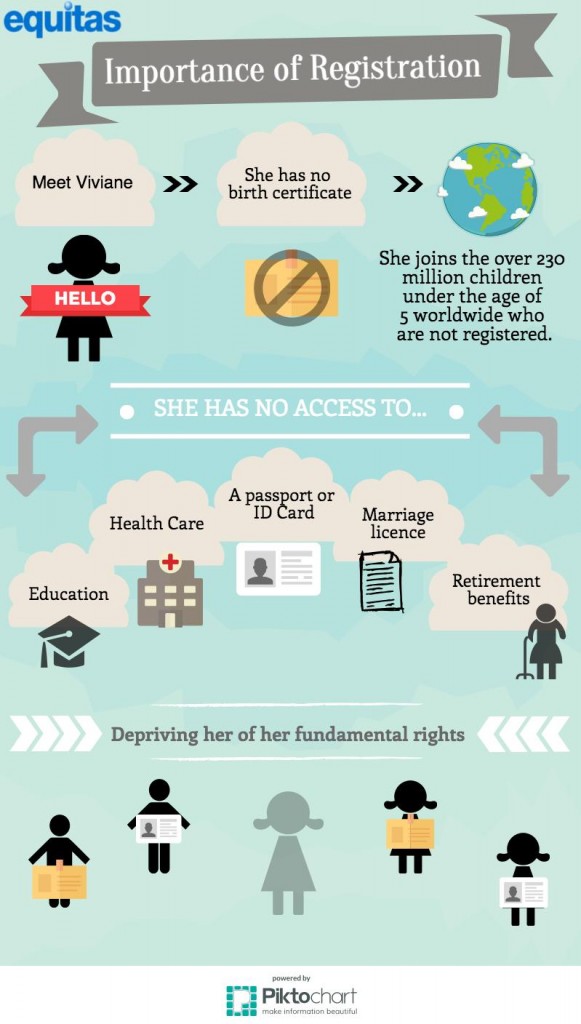

Imagine being deprived of the ability to prove who you are, excluded from society and the global headcount. That’s the reality many people face in developing countries around the globe. According to UNICEF, 230 million or 45 per cent of children under five years old worldwide do not possess a birth certificate. Over 100 developing countries do not have adequate systems in place to ensure public birth registration.  A mobile legal clinic helps people obtain birth certificates and other personal documents in the tea plantation region of Sri Lanka | Credit: Sajeed Ahamed Fahurdeen, Sri Lanka Those who succeed in obtaining their needed documents have to fight tooth and nail to do so. The relief and joy that a birth certificate or identity card can bring is something many take for granted. Lachumanan Rasamany, the man in the photo on the right, knows this feeling all too well. Rasamany, who is now in his 60s, has lived his whole life without a birth certificate. The married father of two girls is smiling wide because he is finally holding his own probable age certificate, which is equal to a birth certificate in function. Former IHRTP participant Sajeed Ahmed snapped the photo above of the plantation worker at a mobile legal clinic held on a plantation in the district of Kotmale, Sri Lanka. It’s hard to imagine the struggles this man and many others have faced due to the absence of this piece of paper. Some of the main reasons why children are not registered at birth include illiteracy, ignorance surrounding the importance of birth certificates, and lack of governmental resources. In Sri Lanka, the acquisition process is time consuming and often takes advantage of those who don’t have the resources to go through it, such as the plantation workers. “The process is not simplified, it is very complicated, even an educated person cannot easily get a birth certificate done if he/she is not registered,” Ahmed said. Birth certificates are essential before anyone can have access to government services. If a little girl is born in Sri Lanka tomorrow and goes unregistered, she will risk the loss of an education, health and immunization, a passport and the ability to move freely. She will get married, but not apply for a marriage license, leaving her in limbo should her husband die, or worse, should she find herself in an abusive relationship. She will face struggles right up to retirement, where she won’t even be able to claim her benefits. The absence of a birth certificate leads to an absence from society; exclusion.

A mobile legal clinic helps people obtain birth certificates and other personal documents in the tea plantation region of Sri Lanka | Credit: Sajeed Ahamed Fahurdeen, Sri Lanka Those who succeed in obtaining their needed documents have to fight tooth and nail to do so. The relief and joy that a birth certificate or identity card can bring is something many take for granted. Lachumanan Rasamany, the man in the photo on the right, knows this feeling all too well. Rasamany, who is now in his 60s, has lived his whole life without a birth certificate. The married father of two girls is smiling wide because he is finally holding his own probable age certificate, which is equal to a birth certificate in function. Former IHRTP participant Sajeed Ahmed snapped the photo above of the plantation worker at a mobile legal clinic held on a plantation in the district of Kotmale, Sri Lanka. It’s hard to imagine the struggles this man and many others have faced due to the absence of this piece of paper. Some of the main reasons why children are not registered at birth include illiteracy, ignorance surrounding the importance of birth certificates, and lack of governmental resources. In Sri Lanka, the acquisition process is time consuming and often takes advantage of those who don’t have the resources to go through it, such as the plantation workers. “The process is not simplified, it is very complicated, even an educated person cannot easily get a birth certificate done if he/she is not registered,” Ahmed said. Birth certificates are essential before anyone can have access to government services. If a little girl is born in Sri Lanka tomorrow and goes unregistered, she will risk the loss of an education, health and immunization, a passport and the ability to move freely. She will get married, but not apply for a marriage license, leaving her in limbo should her husband die, or worse, should she find herself in an abusive relationship. She will face struggles right up to retirement, where she won’t even be able to claim her benefits. The absence of a birth certificate leads to an absence from society; exclusion.  Ahmed believes that there is a general apathy surrounding the right to registration. This negligence, as he refers to it, is brought on by a defunct and disorganized system that drags on for generations. Fatimata Sy is a legal expert and Equitas IHRTP alumnus turned facilitator based in Senegal, a country facing similar registration issues. She recalls meeting an elderly woman whose age was incorrect on her birth certificate. Consequently, she was unable to retire when she wanted to because she could not receive her benefits. “Physically you could tell she was much older than her declared age, but her age on paper allowed her to continue working,” she said. Sy says that this is one of many examples of a system that is outdated and disorganized. She believes work still needs to be done to regulate government offices, ensuring they follow a universal code of conduct. In Senegal, village chiefs are meant to ensure that newborn babies are declared, but Sy says that this important task is often neglected. On top of this, political protests in Senegal back in 2012 led to the destruction of many civil status offices. Sy says that these offices are still in disarray. She recalls recently visiting a centre that had personal files lying on the ground. Records were destroyed, and very little effort has been put into restoring them. According to UNICEF, in West and Central Africa, only 40 percent of children are registered at birth. In Senegal, children are not supposed to be admitted to school without their certificate, but in many cases the rules are bent and they are granted entry. It’s when it comes time to take their exams to obtain their primary school diploma where they face problems. Without proper documentation, they can’t take their exams, receive their diploma and move on to secondary school. “It’s a roadblock for education, it’s a roadblock for the job search, and it’s a roadblock for the liberty to come and go freely,” Sy said. She also mentions that the right to registration is stated in many legally recognized charters, including section seven of The Conventions on the Rights of the Child. Claiming the right to exist It’s a tricky predicament for human rights workers. They are dealing with educating people on the right and importance of registration, but on the other hand, the government makes it tough for people to obtain these documents. Both Ahmed and Sy agree that educating people about their human right to registration is a key factor in mediating the issue at hand. One solution in Sri Lanka comes in the form of mobile legal clinics. Ahmed and the United Nations Equal Access to Justice Project organized clinics in the North, East, and Estate sectors, bringing the process to the plantations in order to help workers register and receive their probable age certificates, birth certificates, and identification cards, as well as educate them about their human rights. This is how Rasamany obtained his documents. A day was set where all the necessary officials travelled to the village in order to issue the certificates, allowing people in the village to wrap the process up into one day, free of charge. “It’s to show that they can issue this document in one day, they don’t have to drag it on for months and months. We try to motivate people to get the documents, and also push officials to do their job properly,” Ahmed said. In Senegal, Sy has trained and supervised paralegals who lead talks about civil status for women’s groups, and she has helped develop the theme for radio show discussions. She believes that human rights education and Equitas’ approach to participatory learning are important, so much so that she’s been partnering up with Equitas on various projects since her involvement in the IHRTP in 2004. “The Equitas approach creates a better experience for them [the participants], they feel more at ease, valued and involved as students. It guarantees a better transfer of knowledge,” she said. With the help of Equitas’ continued presence in the community and training offered as part of the “Strengthening Human Rights Education Globally” project in Senegal, participants in the village of Thiès have tackled the issue of registration head on. Equitas training allowed participants to gain the tools which helped them organize a mobilization campaign to raise awareness on the issue of registration. The goal of the campaign was to ensure students would receive their identity cards in time for upcoming final exams, as well as to empower others to claim their right to an identity. “Each year we were losing students because they couldn’t write their exam, so we knew we had to do this activity to raise awareness and empower people to claim their right,” said Yacine Fall, who works closely with Equitas’ in Senegal. The Attorney General took notice, and has pledged to hold special public hearings on the issue.Fall says that she has seen over 130 cases of missing documents resolved since the process began, and the numbers are still being tallied. Ahmed has been using his IHRTP training in his work with the Equal Access to Justice Project. In addition to the mobile legal clinics, there are also trained Justice Animators who work with people in villages and guide people to getting the proper identification they need to lead fuller lives. He also uses the facilitation skills he gained from the IHRTP in his training of government officers, prison officers and officials. Ahmed says his students come into the training with the ability to point out violations, but with no concrete understanding of how to apply methods of intervention that they’ve learned in the past. He works with them to bridge this gap using Equitas’ participatory approach, using their existing knowledge as a foundation. For now, local human rights workers like Ahmed, Sy, and Fall will continue to address the issue. Sy hopes to see people stand up and claim their right, putting pressure on the government to do their share. “Unfortunately, often in certain parts of our conscience we think it is a privilege,” she said. “The government needs to engage itself to guarantee universal access to registration, in turn respecting its international engagements. They need to provide a system that is reliable for all.” *** This program is undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD), as well as support from Aimia and the American Jewish World Service.

Ahmed believes that there is a general apathy surrounding the right to registration. This negligence, as he refers to it, is brought on by a defunct and disorganized system that drags on for generations. Fatimata Sy is a legal expert and Equitas IHRTP alumnus turned facilitator based in Senegal, a country facing similar registration issues. She recalls meeting an elderly woman whose age was incorrect on her birth certificate. Consequently, she was unable to retire when she wanted to because she could not receive her benefits. “Physically you could tell she was much older than her declared age, but her age on paper allowed her to continue working,” she said. Sy says that this is one of many examples of a system that is outdated and disorganized. She believes work still needs to be done to regulate government offices, ensuring they follow a universal code of conduct. In Senegal, village chiefs are meant to ensure that newborn babies are declared, but Sy says that this important task is often neglected. On top of this, political protests in Senegal back in 2012 led to the destruction of many civil status offices. Sy says that these offices are still in disarray. She recalls recently visiting a centre that had personal files lying on the ground. Records were destroyed, and very little effort has been put into restoring them. According to UNICEF, in West and Central Africa, only 40 percent of children are registered at birth. In Senegal, children are not supposed to be admitted to school without their certificate, but in many cases the rules are bent and they are granted entry. It’s when it comes time to take their exams to obtain their primary school diploma where they face problems. Without proper documentation, they can’t take their exams, receive their diploma and move on to secondary school. “It’s a roadblock for education, it’s a roadblock for the job search, and it’s a roadblock for the liberty to come and go freely,” Sy said. She also mentions that the right to registration is stated in many legally recognized charters, including section seven of The Conventions on the Rights of the Child. Claiming the right to exist It’s a tricky predicament for human rights workers. They are dealing with educating people on the right and importance of registration, but on the other hand, the government makes it tough for people to obtain these documents. Both Ahmed and Sy agree that educating people about their human right to registration is a key factor in mediating the issue at hand. One solution in Sri Lanka comes in the form of mobile legal clinics. Ahmed and the United Nations Equal Access to Justice Project organized clinics in the North, East, and Estate sectors, bringing the process to the plantations in order to help workers register and receive their probable age certificates, birth certificates, and identification cards, as well as educate them about their human rights. This is how Rasamany obtained his documents. A day was set where all the necessary officials travelled to the village in order to issue the certificates, allowing people in the village to wrap the process up into one day, free of charge. “It’s to show that they can issue this document in one day, they don’t have to drag it on for months and months. We try to motivate people to get the documents, and also push officials to do their job properly,” Ahmed said. In Senegal, Sy has trained and supervised paralegals who lead talks about civil status for women’s groups, and she has helped develop the theme for radio show discussions. She believes that human rights education and Equitas’ approach to participatory learning are important, so much so that she’s been partnering up with Equitas on various projects since her involvement in the IHRTP in 2004. “The Equitas approach creates a better experience for them [the participants], they feel more at ease, valued and involved as students. It guarantees a better transfer of knowledge,” she said. With the help of Equitas’ continued presence in the community and training offered as part of the “Strengthening Human Rights Education Globally” project in Senegal, participants in the village of Thiès have tackled the issue of registration head on. Equitas training allowed participants to gain the tools which helped them organize a mobilization campaign to raise awareness on the issue of registration. The goal of the campaign was to ensure students would receive their identity cards in time for upcoming final exams, as well as to empower others to claim their right to an identity. “Each year we were losing students because they couldn’t write their exam, so we knew we had to do this activity to raise awareness and empower people to claim their right,” said Yacine Fall, who works closely with Equitas’ in Senegal. The Attorney General took notice, and has pledged to hold special public hearings on the issue.Fall says that she has seen over 130 cases of missing documents resolved since the process began, and the numbers are still being tallied. Ahmed has been using his IHRTP training in his work with the Equal Access to Justice Project. In addition to the mobile legal clinics, there are also trained Justice Animators who work with people in villages and guide people to getting the proper identification they need to lead fuller lives. He also uses the facilitation skills he gained from the IHRTP in his training of government officers, prison officers and officials. Ahmed says his students come into the training with the ability to point out violations, but with no concrete understanding of how to apply methods of intervention that they’ve learned in the past. He works with them to bridge this gap using Equitas’ participatory approach, using their existing knowledge as a foundation. For now, local human rights workers like Ahmed, Sy, and Fall will continue to address the issue. Sy hopes to see people stand up and claim their right, putting pressure on the government to do their share. “Unfortunately, often in certain parts of our conscience we think it is a privilege,” she said. “The government needs to engage itself to guarantee universal access to registration, in turn respecting its international engagements. They need to provide a system that is reliable for all.” *** This program is undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD), as well as support from Aimia and the American Jewish World Service.